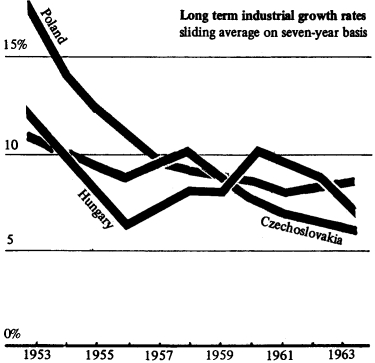

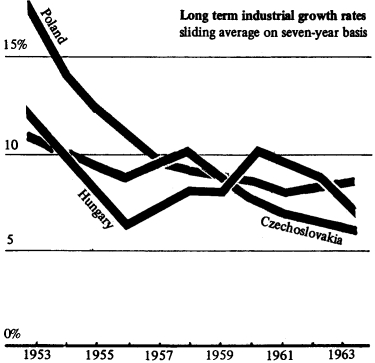

Source: Goldman & Korba, Economic Growth in Czechoslovakia, Prague 1969

From Survey, International Socialism (1st series), No.52, July 1972, pp.5-7.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

Figures on the economic performance of a small country like Hungary are not the sort of thing to hit the headlines. But those issued over the last six months could be of enormous significance for the whole future of the state capitalist countries.

At the beginning of 1968 Hungary’s rulers inaugurated a ‘New Economic Mechanism’, the most radical economic reform yet seen in Eastern Europe outside Yugoslavia. The aim was to deal with a number of failings that plagued the economy – as they plague the economies of all the Stalinist states, particularly the more economically advanced ones. The most obvious was the tendency for long term growth rates to decline.

But that has not been the only problem. The overall growth rates conceal enormous disbalances and wastages inside the economy. In Czechoslovakia in the years 1956-65 ‘a large part of accumulation – close on a third – was tied down in inventories and capital under construction’. In Poland 28 per cent of accumulation was in inventories alone. [1]

Instead of being available for consumption or investment, products pile up in warehouses or are tied down in massive construction sites that are years overdue on completion. The drain on resources that results is massive. One estimate is that 5-7 per cent of the output of the economies of Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland is lost in this way. [2]

For the rulers of these countries some answer to such wastage has become more necessary as the overall growth rates get smaller. How does the wastage arise?

All the bureaucratically centralised economies display a drive to repeatedly embark on investment plans on a scale that cannot possibly be accomplished in the planned time, given the resources of the economies. At the beginning of each five years a series of massive investment projects are begun. But it soon becomes clear that shortages and bottlenecks are going to prevent them being finished on time.

The overambitious projects run up against what is sometimes called the ‘raw material barrier’. [3]

The initial period in which investments soar is now followed by a period in which growth rates stagnate, and some projects are left to rot unfinished while resources which were initially meant for them are transferred elsewhere. Projects which they in turn were meant to supply with inputs, even if completed, are unable to operate at full capacity. While some projects are held up by shortage of resources, others produce goods for which there is lack of demand. The overall result can even be a decline in the total social product, as in Czechoslovakia in 1962-3, when ‘a policy of very big new investment plans in the metallurgy and chemical industry led to a sudden 2-3 per cent drop in the national income.’ [4]

|

|

Source: Goldman & Korba, Economic Growth in Czechoslovakia, Prague 1969 |

Perhaps even more important are the social and economic consequences of the emergency measures employed to try and rectify the situation. On the one hand threats arise to the political stability of the regime; on the other any possibility of rationally organising the economy in the long term is destroyed. The search for resources to complete ‘priority’ projects invariably means an attack on workers’ living standards. The projects that are abandoned or frozen are usually those concerned with increasing consumer good or food production. Increases in imports of raw materials or components for industrial projects have the same effect: they are paid for either by cutting food imports or by reducing the level of consumption so as to allow greater food exports.

The central management of the economy can only deal with the problem in two ways:

- By obtaining the necessary resources from abroad by raising imports.

- By scrapping or freezing certain projects and using the resources initially allocated for them to other, ‘priority’ projects.

In this way, the original, optimistic predictions about growth rates are soon invalidated.

‘Analysis of the dynamics of industrial production in Czechoslovakia, the GDR and Hungary supplies an interesting picture. The rate of growth of industrial production shows relatively regular fluctuations ... These fluctuations are still more pronounced if the analysis is confined to producer goods.’ [5]

In extreme cases such measures result in deep social unrest. During the Hungarian First Five Year Plan (1950-55) the attempt to maintain a disbalanced investment programme meant that ‘the real value of wages diminished by 20 per cent’ [6]; in October 1956 the Hungarian workers took their revenge. Years of declining living standards followed by an attempt to cut the meat consumption (so as to raise exports to get desperately needed foreign currency) prepared the ground for the uprisings 18 months ago on Poland’s Baltic coasts. The economic dislocation of the mid-sixties was the necessary background of the Czech ‘spring’ of 1968.

The attempts to deal with the short term economic difficulties also aggravate long term problems. The abandonment and freezing of some projects inevitably means that overall economic development is unbalanced and one sided: it is not unusual to find that when a highly expensive factory is completed it cannot operate at full capacity because a project producing some essential input for it has not been finished. [7]

Whatever talk there might be of ‘five year planning’ nationally, at the factory level a manager hardly knows from one week to the next what he will be expected to produce and in what quantities. If he starts work on one project, there is a strong likelihood he will soon be ordered to scrap existing production plans and start producing for another priority.

At present the allocation of tasks at the factory is not even planned on a yearly basis – as is clear from a statement by Baibakhov, the Chairman of Gosplan:

‘It is essential that the basic form of the planned development of the national economy must be a five year plan, with an annual allocation of the most important tasks ... These requirements have not yet been fully implemented.’ [8]

Faced with such uncertainties, it is hardly possible for the manager to plan the work of his factory on the most efficient basis. Instead, he develops a strong interest in making sure he has excess hidden labour and raw material resources. Then he can make sudden and unplanned switches from one production line to another, from one quantity of output to another, without over-exerting the workforce or the plant. It also means he has an interest in being as little dependent upon outside supplies as possible – hence a marked tendency for enterprises to make as many as possible of the goods they need themselves, regardless of the cost, rather than rely on supplies from outside that might not be available when needed.

The overall result is that any rational calculation of what resources are available in the economy becomes impossible; no real incentives exist at the factory level to increase productivity, despite continual admonishments from the authorities; and conditions are created in which there is no real way of telling whether future investment targets correspond to the resources of the economy.

Of course projects which are delayed do eventually come in to production. Then a massive burst in industrial growth follows. But it is no more planned than was the previous downturn. And it cannot cancel out the other irrationalities in the economy. It does however, have one invariable effect: it prompts the central authorities to overestimate the speed at which future investment is possible and to repeat their previous setting of vastly over-ambitious investment plans.

The aim of schemes of economic reform in the Eastern Bloc countries has been, quite simply, to do away with the disproportionalities and pave the way for balanced growth at a reinvigorated rate. Their proponents argue that the only way to overcome the imbalances and irrationalities is to develop some sort of market mechanism to relate the outputs of different enterprises to each other and, eventually, to the outside world. Then, it is said, the managers will have an incentive to relate their investment plans to those of the needs of consumers and other enterprises, and they will also be forced to adopt a realistic pricing policy, which reflects real production costs.

In the late 1960s there were moves towards the partial implementation of such a programme in many of the Stalinist states. Reforms were pushed through in Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Poland, and even in Russia itself. But they were usually limited in scope by the resistance of strong vested interests inside the bureaucracy. In Czechoslovakia the economic reforms were finally abandoned two years ago with the reimposition of tight bureaucratic control.

So far the Hungarian reforms have avoided such a fate and have been much more far reaching than those suggested elsewhere. The attitude of western experts to the reforms until recently was one of unqualified approval. The reforms seemed to justify the faith of bourgeois economists in the market mechanism as the only possible basis for organising an industrialised society. There was hardly a hint that the Hungarians might have solved nothing with their ‘reforms’.

Yet last August it began to be revealed that the old faults of the state capitalist economy were re-emerging in a scarcely changed form. Rezso Nyers, the head of the Communist Party’s economic department presented a report that indicated that ‘current investment expenditure in Hungary appears to have broken all bounds and is running 23 per cent higher than during the first half of last year’. [9]

The president of the Hungarian National Bank reported that funds tied up in unfinished investments amounted to 65,000 forints – more than the total investment expenditure for the year. [10] In October the prime minister Fock indicated that ‘investment had gone up twice as fast as the national budget and the balance of payments. Too frequently investments were being embarked upon which were not feasible either technically or financially’. [11] Reports have since revealed that last year imports grew at twice the pace of exports, with imports of plant and machinery doubling. The overall investment rate was ten per cent higher than planned. [12] Meanwhile, only 11 put of 19 planned investment projects had been completed. [13]

Faced with these difficulties, Hungary’s leaders seem to have little choice but to revert to old remedies – even if these are bound to give rise to all the old side effects. Fock has announced that the reforms will continue – but with ‘closer control from the centre’. In other words, there will be partial moves back to the old bureaucratically centralised system. The banks have been given orders to give credits only to ‘uncompleted or top priority investments’. At least two major investment projects due for this year will not now go ahead.

The immediate political consequences for Hungary of this state of affairs are difficult to predict. Internally there are already reports of some unrest, with clashes between demonstrators and police on the streets of Budapest for the first time for 16 years. Economic pressures seem to be affecting the country’s international stance as well. Hungarian ministers have let it be known that trade negotiations with the Russians are not going too well. It seems that Russia, which accounts for two thirds of Hungary’s trade, is not taking sufficient account of that country’s short term problems or medium term needs. But it is too early yet to tell whether these are portents of a major social and political crisis on the scale of 1956 or 1968.

However, what is clear is that the balance sheet of Hungary’s reforms is of enormous significance for the long term development of the whole Stalinist world. It indicates the fallaciousness of the belief that there is some magical property in the market mechanism which will enable the bureaucracy to turn to it, belatedly, as a solution to its growing problems.

It does not require any great insight to see why the reforms solve nothing. The roots of the contradictions which beset the bureaucratically centralised economy lie in the drive to accumulate means of production on a scale that bears no relation to the real resources of society. But this drive is not the result of some arbitrary whim of the central planner or of some deficiency in the planning mechanism. It follows rather from the fact that the bureaucracy exists as a ruling class trying to maintain and extend its control in competition with other ruling classes internationally.

The rulers of the Russian bloc are driven to jack up production because of their desire to defend their empire against the rulers of other powers – America, and increasingly, China. It is an important fact, even though it does not accord with the mythologies of many on the left, that there are now 44 Russian divisions on the Chinese frontier, compared with only 31 in Europe. The arms race necessitates an endless drive to accumulate at a speed not determined by internal resources but by the international balance of forces (in turn a reflection of the international level of productive forces). That also explains why ‘priority projects’ are so rarely in the consumer sector. They do not contribute to increasing military potential.

The East European states have to bear an increasing part of this burden. Since 1949 they have faced an average annual rise in their military expenditure of 7.5 per cent a year (compared with 4.1 per cent for the USSR). [14]

In recent years such expenditure has further escalated, with a total of 52 per cent increased military spending by Warsaw Pact countries other than the Soviet Union between 1965 and 1970. This figure must explain at least some of the over-ambitious investment projects and the stagnating or even falling living standards workers have had to put up with. But in the case of the East European states there is another factor also at work.

All of them are heavily dependent on foreign trade. And in foreign markets even within the Soviet bloc, they have to compete not only with western firms, but also with each other. There is virtually no trans-national direction of the industries of Eastern Europe.

To survive in such economic competition the rulers of these states are subject to exactly the same compulsion as that which confronts private capitalists in the west – ‘accumulate, accumulate, that is Moses and all the prophets.’

It was precisely under the classical market of the west that this drive to accumulate periodically outstripped the resources to sustain it profitably, plunging the economy into a slump. [15]

There is surely no reason to believe that the partial introduction of market mechanisms into bureaucratically centralised economies will end their propensity to disproportionate and cyclical development. [16] Only the establishment of an economy no longer dominated by the exigencies of international competition can do that. And that requires first of all the destruction of the national bureaucratic ruling classes as part of the process of international revolution. No amount of reform is a substitute.

But if economic reform does not work, then the sorts of convulsions that have shaken Eastern Europe in the past will inevitably recur in the future. They will also increasingly take their toll in Russia itself, as the high growth rates and the massive spare labour and material resources that previously hid the extent of economic failings become a thing of the past. Whatever the consequences for Hungary itself, the failure of reform indicates that the time may not be far off when Moscow and Leningrad experience their own 1956.

1. Goldman and Korba, Economic Growth in Czechoslovakia, Prague 1969, pp.68-9.

2. I.T. Berend, Background to the Recent Economic Reforms in Hungary, East European Quarterly, vol.2 no.l; J. Fekeke (of the Hungarian National Bank) gives an estimate of 8 per cent wastage for Hungary 1961-4 in Grossman (ed.), Money and Plan, p.65.

3. A term introduced by the Polish economist Kalecki, used by Goldman and Korba (op. cit.) and also by Kuron and Modzelwski in An Open Letter to the Party.

4. Karel Cerny (of the Institute of Politics and Economics, Prague) in East European Quarterly, vol.3 no.3, p.346.

5. Goldman and Korba, ibid., p.41.

6. According to Berend of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, ibid., p.83.

7. The most famous example of this was probably when the effect of a large increase in fertiliser production in Russia was to a certain extent annulled by the shortage of paper bags to hold the fertiliser.

8. Speech of 1 October 1968.

9. Financial Times, 9 August 1971.

10. Ibid.

11. Quoted in Financial Times, 26 October 1971.

12. Financial Times, 4 February 1972.

13. Economist Intelligence Unit, Quarterly Review, Czechoslovakia v. Hungary, 1972, vol.2.

14. SIPRI Year Book 1969. However, total spending on arms is still probably at about half the Russian level. The Institute of Strategic Studies publication, Military Balance, suggests a level of 5-6 per cent of the GNP – about the British level of arms spending.

15. An investment boom would force up wages and raw material prices until further investment (or even completion of existing investments) became unprofitable. Producer goods industries would then find no outlet for their products and a general closing of factories, laying off of workers etc would follow. This pattern was only smoothed out when investible resources began to be diverted into channels which did not contribute to productive capacity of society – cf. Michael Kidron, Western Capitalism Since the War. There are clear similarities between this classical cycle and the cycles which prevail in the state capitalist countries. Eastern bloc economists like Goldman and Korba have tried to deny this by arguing that ‘in a capitalist economy deceleration is due, as a rule, to deficiency in effective demand, the opposite applies to a socialist economy’. But this would seem to ignore the cause of ‘deficiency in effective demand’ in the private capitalist economy – the bunching of new investment in such a way as to cause a temporary rise in wages and material costs and a temporary fall in the rate of profit (not to be confused with the long term decline in the rate of profit due to the changing organic composition of capital). For Marx’s exposition of these points see Capital, vol.3, p.253.

16. A point which is borne out by the behaviour of the Yugoslav economy, which has undergone reforms far greater than those considered anywhere else in Eastern Europe. The Yugoslav economist Branko Horvat has pointed out that ‘the Yugoslav economy is significantly more unstable than any of the ten (major) economies ... including the US’. He estimates that but for cyclical downturns in the economy, Yugoslavia’s GNP would have grown 25 per cent more in the period 1952-67 than it actually did. Cf. B. Horvat, Business Cycles in Yugoslavia, translated in Eastern European Economics, vol.IX, no.3-4.

Last updated on 16 November 2009