Winfried Wolf Archive | ETOL Main Page

From Intercontinental Press, Vol. 17 No. 24, 10 November 1979, pp. 1138–1144.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

Is the sixth largest automotive producer going to buy out the third largest? Volkswagen (VW) is a company in robust health, swimming in the liquidity of billions of Marks. Is it going to swallow up the faltering Chrysler Corporation, which has been showing huge deficits? There was a sensational report to this effect in the financial press at the end of June 1979.

A price was even mentioned – a “mere” 1.9 billion marks. Volkswagen should not have any difficulty in putting that much money on the table at a time when production and profits are increasing. However, the report was strongly denied by both the Wolfsburg and Detroit trusts. For the moment at least, the deal has not been concluded.

Nonetheless, this affair has shed a harsh light on the situation in the world automobile industry, in which up to now there had seemed to be no limits to the expansion. But now an acute crisis of competition is shaping up. While the European trusts are stepping up their competition within the Common Market, VW is trying to make a breakthrough in the American market.

At the same time, the Japanese are biting off a bigger and bigger share of the West European market. Of course, they are going about this less aggressively but with “greater sensitivity.” And they are looking ahead to making direct investments in West Europe.

In this period, the two American giants. General Motors and Ford, are preparing for an offensive in the small and medium car field in the West European and American market. For that purpose they have launched massive investment programs.

There are also some newcomers to make this picture of competition even more crowded – the automotive producers in the East European countries and in South Korea. Two immediate conclusions can be drawn. First, the world automotive industry is going to undergo restructuring processes of considerable scope. Secondly, the new investment programs are going to lead to enormous surplus productive capacity, that is, a new worldwide crisis of the automotive industry.

This scenario shows striking similarities to the 1973–75 crisis. In 1973, the so-called oil crisis (that is, the higher prices of oil and raw materials) lent an inflationary character to the economic boom.

Of course, the higher prices for gasoline did not directly affect the boom in the automotive industry, but they had already become a factor in the nascent crisis of the industry. This boom generated surplus productive capacity on the world scale. The automotive market could no longer absorb this productive capacity. The market was beginning to become saturated.

In 1975, the automotive industry was experiencing its deepest crisis, just at the time when, as a result of the general recession, declining purchasing power on the part of the workers, unemployment, stagnating wage levels, and the tightening of credit reinforced all the other elements of crisis. Today, the new “oil crisis” of 1978–79 may very well be the omen of a new crisis in this industry and in the capitalist economy as a whole.

We will analyze these developments below.

The automotive industry occupies a special place in the economic structures of the United States, Japan, France, West Germany, Italy, and Britain. These six countries, in which 80% of world automotive production and 75% of demand are concentrated, are marked first of all by the “structural weight” of the automotive industry. This sector accounts for between 5% and 8% of total industrial production. It accounts for one-tenth, or more, of the exports of all these countries (see Table 1).

But these figures do not come close to telling the whole story. The real weight of the automotive industry in these countries is much greater than it would first appear. For example, according to a study done by the Common Market, at the end of 1975, the automotive industry directly employed about 1.3 million workers.

In addition, 1.8 million workers were employed by parts plants and subcontractors to the automotive industry. Another 1.6 million workers are employed in selling and servicing motor vehicles. These two categories together amount to two and a half times the number of workers employed in the automobile plants. (Frankfurter Rundschau, December 30, 1976.)

TABLE 1

|

||||

|

Country |

Number of |

% of total |

% of total |

% of total |

|

France |

250,000 |

5 |

5.9 |

10 |

|

W. Germany |

600,000 |

8 |

6.9 |

12.5 |

|

Britain |

480.000 |

6.3 |

5.9 |

10 |

|

Italy |

200,000 |

4 |

5.2 |

10 |

|

U.S.A. |

– |

– |

6.0 |

– |

|

Source: Le Monde, July 3, 1979. |

||||

In West Germany, the metalworkers union (IG Metall) and the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) estimate that in 1975 “the jobs of 5% of all West German wage earners, or about 1.4 million wage earners out of a total of 26.4, depended on the level of demand in the market for motor vehicles.”

The figures for other countries are similar. Le Monde has estimated the number of workers dependent on this industry, including those directly involved in automotive production, at one million in Britain and 500,000 in Italy.

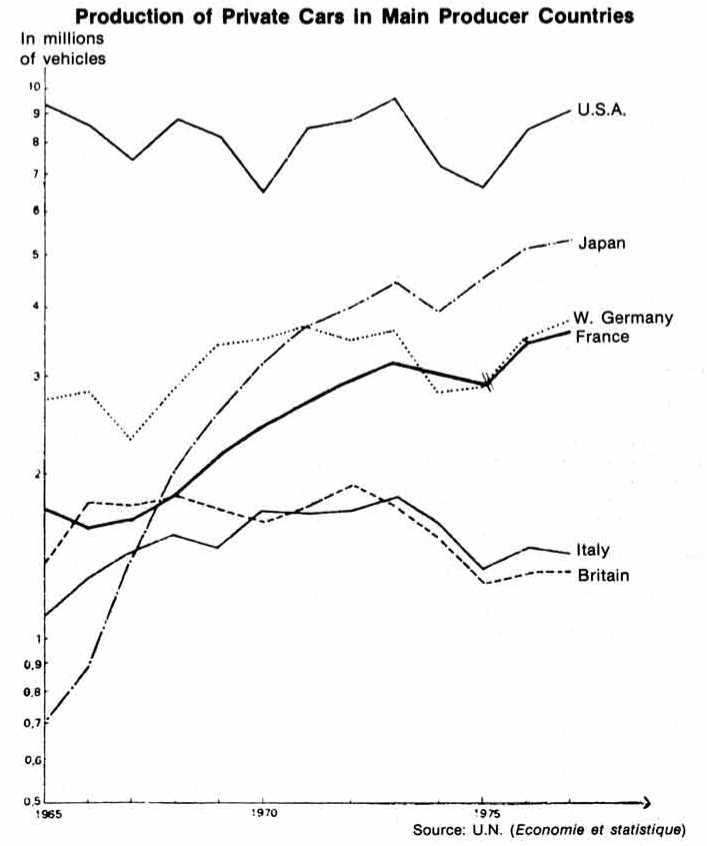

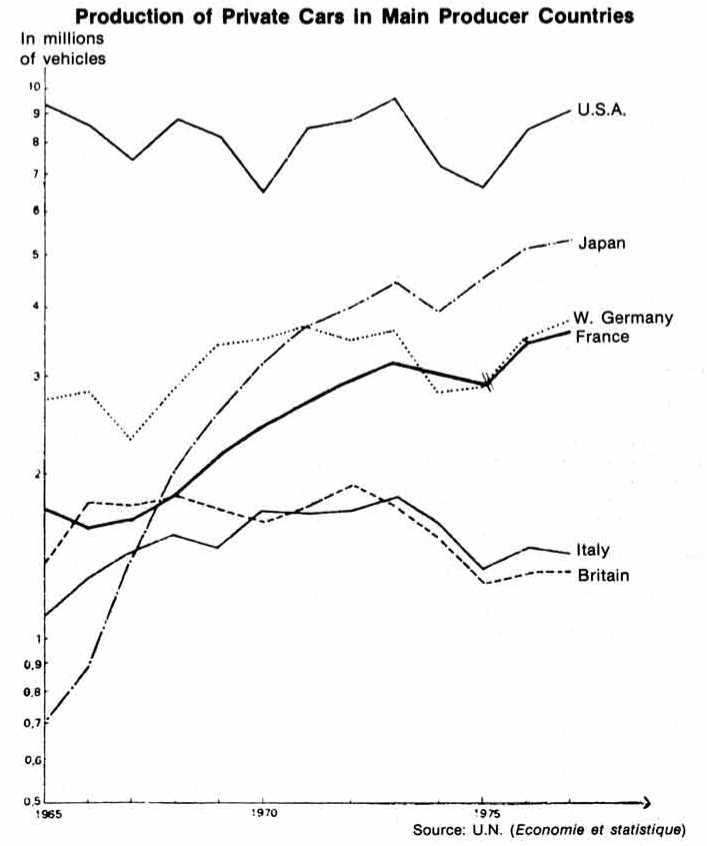

While the weight of the automotive industry in the big producer countries is, in general terms, quite similar, the trend in this branch has differed considerably from country to country.

In France, West Germany, and above all Japan, the relative weight of automotive production in overall production has steadily increased. But in Italy and Britain the relative weight of automotive production has not grown, and in the United States it has actually declined.

Thus, in the decade from 1950 to 1960 the annual growth rate of automotive production in West Germany averaged 18.5%, while overall industrial production increased only an average of 10.5% annually. In the 1970s, these rates have been 8.1% and 6% respectively (IGM-Studie).

In France automotive production increased at an average annual rate of 12.7% between 1959 and 1977, while overall industrial production increased 11.2%. For the same period, the growth in investment in the French automotive industry was 13.5%, as against 13% in the economy overall. These figures are annual averages. (Economie et Statistiques, no. 104, October 1978, Paris)

These very different trends have had important consequences in shifting the relative weights of each national automotive industry in worldwide production (see Table 2).

The sharp differences in the share of world production held by the various countries are in some respects specific to the automotive industry. France illustrates this, since it has clearly improved its position in recent years. On the other hand, the development of this industry displays certain general characteristics of the imperialist structure.

When people talked about the crisis of the automotive industry in 1974–75, the expression “saturation of the market” was frequently used. In the United States there was one car for every 2.2 persons and in West Germany one car for every 3.7 persons. The industry had reached a threshold that seemed difficult to surmount.

TABLE 2

|

||||||||

|

Country |

1937 |

1951 |

1955 |

1961 |

1965 |

1970 |

1974 |

1976 |

|

U.S.A. |

78 |

77 |

72 |

53 |

49 |

29 |

29 |

29.2 |

|

Britain |

8 |

7 |

8 |

11 |

9 |

7 |

6 |

4.6 |

|

France |

4 |

5 |

5 |

9 |

7 |

10 |

11 |

10.2 |

|

W. Germany |

5 |

4 |

7 |

14 |

14 |

16 |

11 |

12.2 |

|

Japan |

– |

– |

– |

1 |

4 |

14 |

16 |

17.3 |

|

Italy |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

7.6 |

6.5 |

5.1 |

|

Source: IG Metall, Studie and Statistisches Jahrbuch der BRD 1978. |

||||||||

“The automotive industry ... is experiencing a rate of growth today markedly lower than in the 1950s and 1960s. This confirms that the great expansion of this industry is coming to an end ... and that demand is more and more limited to the need to replace cars already sold.”

Ernest Mandel made these observations in the late 1970s. [1]

The German metalworkers union declared, although this was nothing but empty words spoken for obvious reasons: “We are still far from having saturated the German market.” But it could not fail to recognize that there had been “an exceptional decline in the average rate of growth in the automotive industry” or that there had been a “change in the strategy of the employers, who are now trying to increase not the number of vehicles produced but the prices.”

In fact, however, in most of the big automobile producing countries the growth rates of this industry set new records in the period 1975-79. In West Germany, the annual growth rate has been around 10%, notably higher than in the 1960s. On the other hand, if you look at the period 197079, that is including the crisis of 1974, the annual growth rate is around 7%, that is, a little below the average in the preceding decade.

But everywhere the density of automobiles has increased. In the United States, it reached the point in 1978 that there was one car for each 1.5 inhabitants (Le Monde, July 3, 1979). In West Germany it was one car for every 3 persons; in France, one for 3.1 persons; in Italy, one for 3.3; and in Britain, one for 3.8 persons (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, February 24, 1979). So, in 1980, West Germany will have 23 million cars. A 1975 Shell Oil Company Btudy estimated that this figure would be reached only in 1990, which a new study in 1977 then revised to predict that this total would be attained in 1985.

The statistics on this new growth in the density of automobiles and on the absolute increase in the number of registered vehicles show that what is going on is not simply, or even mainly, a process of replacing and updating the present fleet of automobiles, although this plays an important role.

It is evident that the abstract concept of “saturation” depends far too much on the use value aspect of the automotive product. It neglects the possibilities for increasing the value itself. That is, this concept does not take sufficient account of the anarchy of capitalist production. One car for 1.5 inhabitants, as is the case in the United States (and this ratio is computed on the basis of the total U.S. population, including children), does represent waste from the standpoint of the society as a whole. Even if you accept the idea that individual private vehicles should be the main means of transport, which we do not, these figures indicate that a point of “natural saturation” has long since been reached.

However, in a society that does not plan public transportation, a society where the automobile industry itself blocks such planning, a society that as a general rule assures that individual cars are a cheaper and more comfortable means of transportation than public transport (in the U.S. many big cities have no public transport at all), in such a society the sort of trend described above becomes quite possible. The only criterion, then, is the demand on the market.

Over the past four years, there has been such demand on the market. In this period, after years of belt tightening, real wages increased slightly. In absolute figures, employment rose, as it did in the U.S. And credit was loosened.

On the other hand, there has been an absolute, or at least relative, stagnation in the development of public transportation. In West Germany, for example, where, unlike the United States, there is a relatively well developed network of urban and interurban transport and where only recently quite considerable investment was made in this system, the number of persons using public transport dropped by 0.5% in 1978, by comparison with 1977. In 1979, there seems to have been no increase in the number of users.

In contrast to this picture in public transport, in the last two years individual transport has increased by 11%. A similar picture emerges as regards freight. In 1979 road transport has grown by 13.5% compared to 1977, while rail transport has increased only 8% (Kommerzbank Branchennotiz, March 9, 1979).

So, what has become of the official preaching about the need to “accept the consequences of the energy crisis?” In view of the sort of development described above, the heated discussions over reducing the speed limit in Germany begin to look strangely like a charade.

A new boom would also mean stepped up competition, more surplus capacity, and finally a new crisis. The evolution of the international automotive industry already foreshadows this (see Tables 3, 4).

TABLE 3

|

|||

|

Country |

1965 |

1977 |

Increase |

|

1. Japan |

101 |

2,959 |

× 29.3 |

|

2. Canada |

78 |

886 |

× 11.4 |

|

3. U.S.A. |

106 |

688 |

× 6.5 |

|

4. France |

489 |

1,621 |

× 3.3 |

|

5. Italy |

308 |

644 |

× 2.1 |

|

6. W. Germany |

1,419 |

1,939 |

× 1.4 |

|

7. Britain |

628 |

475 |

× 0.7 |

|

Source: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. |

|||

First of all, these figures confirm what was said previously about the vigorous offensive the Japanese automotive industry has been waging. According to Table 3, Japanese automotive exports increased by nearly thirty times between 1965 and 1977! However, one is immediately struck by one important difference. Table 2 shows that U.S. automotive production has declined as a percentage of world production. But in the period 1965–77, as shown in Table 3, the export of U.S. cars has soared, growing more rapidly than exports of their Common Market competitors.

To be sure, a large part of these larger U.S. exports resulted from the increasing industrial relationship between the United States and Canada, that is, from the automobile business within North America. Likewise, it has to be kept in mind that at the beginning the volume of automobile exports from North America was very low. By 1977, the exports of the United States and Canada were still lower than those of West Germany or France. But these figures also partially reflect the first counterattacks of the American automotive industry against the Japanese and European offensive.

Table 4

|

||||

|

Year |

France |

W. Germany |

Britain |

Italy |

|

1966 |

13.9 |

13.6 |

5.1 |

14.3 |

|

1970 |

19.9 |

22.5 |

14.3 |

31.3 |

|

1975 |

20.3 |

24.9 |

33.2 |

31.4 |

|

Source: Economia et Statistique, October 1978. |

||||

The figures in Table 4 also reflect a situation of stepped-up competition. In the four Common Market countries cited, in the period 1966–75 automobile imports doubled in Italy and West Germany, and grew in Britain by six times. The French automotive industry was the most successful in protecting itself from foreign competition. In the case of France, imports in that period rose only by 50%.

The competitive struggle in the international automotive industry was opened up by the offensive launched on the export market by the Japanese and European automobile producers, which was directed at the American market. This offensive was marked by the spectacular success of the VW “Bug” and later by the Japanese small cars on the American market and was the outstanding feature of the 1960s. It brought about, as already pointed out, the breakdown of the American domination of auto production. But from an overall standpoint, the American giants were not worried.

Initially, there was even a sort of “division of labor.” The small and mediumsized car field was largely conceded to the Common Market and Japanese producers. In the field of the big “medium-sized” cars and the traditional six- and eight-cylinder cars, which was still decisive for the U.S., American supremacy remained unassailable.

Moreover, from the early 1960s on, the decline of the dollar helped decisively to protect the “big three” – General Motors, Ford, and, at that time, Chrysler – from Japanese competition.

This situation changed with the onset of the automobile crisis and the “oil crisis” in 1973. Since then we have seen major restructuring in automobile production. At the start, the shift benefitted the U.S.’s foreign competitors. So, when Volkswagen set up its own plant in the U.S., it seemed that war had been declared. American industry took up this challenge, and in turn declared war on its competitors. In mid-1977 it announced its investment programs in Europe. This operation must now be analyzed.

Starting in the mid-1970s, several factors changed the situation in automotive production. First, in the advanced capitalist centers, conditions arose that more and more put in question individual transportation in cars (long tie-ups in rush hours, parking problems, the creation of pedestrian zones in the city centers).

Moreover, while the “oil crisis” of 1973 was certainly deliberately exaggerated, it nonetheless reflected a potential shortage of gasoline, and it brought on a relatively rapid rise in price that is now constantly on the minds of drivers.

Finally, the widening of the crisis of capitalism in decline has aroused a growing awareness of the environment and provoked broad opposition to pollution as a factor that is destroying the conditions for human life. This has not taken long to produce results. Some very severe measures have been taken affecting the technology and regulation of the new automobiles now being put into service as well as the fuel used in them. Safety measures are more and more rigorous. The lead content of gasoline has been reduced and rationing has been introduced.

The first consequence of this situation that should be noted is a general increase in the prices of cars and other individual vehicles. This contrasts with the previous period when they remained usually relatively cheap. The result has been a massive rush toward small and middle-sized cars.

At the same time, there was a turn away from the “big tanks” that had dominated the American market. The European and Japanese cars got 30-40 miles per U.S. gallon of gasoline, about twice or more what the American cars did. Moreover, small diesel cars were developed, including the famous Volkswagen Golf diesel [marketed in the U.S. as the Volkswagen Rabbit], whose price was particularly favorable. Since then, there has been experimentation with new diesel vehicles that get 70 or more miles to the U.S. gallon.

The restructuring gave an immediate advantage to the European and Japanese companies in the North American market, as well as in all other world markets. In the U.S. imported automobiles at one point took 25% of the market. It is the Japanese who have benefitted the most. In 1976, Nissan motors sold half of their production abroad and 35% in the U.S. Of the 4.5 million Datsuns made in 1977, about 900,000 were sold in the U.S.

In 1977, the U.S. launched a counteroffensive. It began with an attempt to reconquer its own internal market by building small and middle-sized cars (for example, the Chevette). Since 1977, they have succeeded in underselling the imports because the rise of the Mark and the Yen has forced their Japanese and German competitors to increase their prices. The share of the market held by imported cars rapidly declined from the peak of 25% to levels as low as 10% in some years.

Volkswagen sales declined spectacularly. After the records set in the early 1970s, when VW sold up to 500,000 vehicles a year in the U.S., sales dropped below 200,000 from 1975 to 1977.

The VW-Chrysler affair, to a certain extent, reflects these structural changes and their consequences.

The Chrysler Corpotation, the world’s third largest automotive producer, has not been able to cope with these structural changes. It should be noted that its product line is even more dominated by the “big tanks” than the Ford and GM trusts. The new regulations aimed at reducing gas consumption and increasing safety, and the changes in the type of vehicles that this entails, alone will force Chrysler to make capital investments of 4 billion dollars in the period 1978–83.

Chrysler has been sinking deeper into losses and debts. In 1975, for example, it experienced the biggest losses in the history of the American automotive industry, running a deficit of 260 million dollars. In 1978, its share of the market fell from 17% to 12%, and it lost nearly 205 million dollars. But its share of the internal market has risen back to the level of 15% (Wirtschaftswoche, July 2, 1979).

In the current year, Chrysler announced it expected to lose the colossal sum of 700 million dollars. So, it has begun a spectacular worldwide retreat. In August 1978, it announced that it was selling all European Chrysler operations to the Peugeot-Citroen group. Chrysler/Europe was mainly made up of Simca-Matra, Chrysler/United Kingdom, and Chrysler/Spain. In 1977, annual production was around 774,000 vehicles, or about a quarter of the total Chrysler production.

Before taking over Chrysler’s holdings, Peugeot-Citroen produced 1.5 million vehicles. In return for this move, Chrysler got 230 million dollars and a 15% share in the French group, which has now been catapulted into first place among the European automotive trusts (ahead of VW) and into third place worldwide, ahead of Chrysler, Toyota, Datsun, and VW (Handelsblatt, August 14, 1978).

Six months later, VW absorbed Chrysler/Brazil, which along with passenger cars produced two kinds of business vehicles from its Dodge truck line. Thus, VW has become the unchallenged number one producer of cars in the largest Latin-American market (before buying out Chrysler, VW already held 51% of the market). It also got a serious foothold in the contest to win the truck market in North and South America. (Chrysler’s share of the Brazilian truck market was 2.3%. Handelsblatt, January 26, 1979.)

In this period, Chrysler is concentrating on the U.S. market and pushing production of two medium-sized cars, the Omni and Horizon, which are competitive models that can meet the present and the likely future official requirements and regulations. But the trust is not financially strong enough to produce both the engines and the automatic transmissions for its models. For that reason Chrysler signed a contract of cooperation with Volkswagen, which is to deliver 300,000 Golf engines for these cars.

Moreover, at the end of July there was a report that VW is going to buy Chrysler/Argentina, which would open the door to the second biggest market in Latin America, one that had previously been closed to VW. The Argentine market was previously dominated by Chrysler, FIAT, Daimler-Benz, and Renault (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of July 14, 1979).

While Chrysler is cancelling its international contracts and falling back on the American market, and even there is threatened with bankruptcy, VW is growing and becoming a multinational corporation. In 1976, the directors of the Wolfsburg trust decided, after long hesitation, to challenge the American automotive trusts in their own country.

VW invested 1.2 billion Marks to start up production in the United States. There was no other way, according to the trust’s strategists, to stem the effects of the fall of the dollar and the decline in their sales in the United States. (The rate of exchange between the dollar and the Mark was 1 to 3.65 in 1970; 1 to 2.59 in 1974; and 1 to 1.80 in 1978.)

The success achieved by VW in 1978 and 1979 proved the correctness of its decision. VW sales in these years were 300,000 and 380,000, approaching the previous records. Most of these cars came from the factory in New Stanton, Pennsylvania, a newly-built, but never operational, plant taken over from Chrysler, which is symptomatic. After a year of production, this factory reached its maximum capacity in producing Rabbits (Golf) and could no longer keep up with the demand. Moreover, there were several strikes in this factory, which is run by the former Chevrolet manager, James McLernon, who is both an ambitious person and a demagogue. It seems that in mid-1979, plans were drawn up for a second factory involving a 5 billion Mark investment (Frankfurter Rundschau, June 19, 1979).

In this context, “a merger in the United States between VW and Chrysler would have a certain logic,” Wirtschaftswoche noted in its June 25, 1979, issue. It made this comment following the first rumors of the merger, which were published in the American magazine Automotive News. It seems that for the moment there is no question of VW buying out Chrysler completely, as had initially been reported, at least not for the low price of two billion Marks. VW would rise to the rank of the second or third largest automotive producer in the world, behind GM and Ford. It is unthinkable, in these conditions, given the sharpening international competition, that the American government would not intervene. [2]

It is much more realistic to envisage close collaboration between Chrysler and VW, perhaps with VW buying a portfolio of Chrysler stock, entering into new contracts for cooperation, and building joint factories. There is already talk of a joint factory to build both engines and transmission systems.

The result would be essentially the same as in a full merger. In collaboration with Chrysler, VW would rise to the same level on the American market as the two giants. Ford and GM. Chrysler would get the financial means to carry out its plans for restructuring and would overcome the gaps in production technology, with VW’s help in the area of motors.

All these news reports and the general situation seem, first of all, to demonstrate definitively that the automotive industry in the United States is in a precarious position. In fact, the journalistic accounts of this situation have often been very onesided. The following is an example: “The empire of the American trusts in Europe was often called the third-biggest industrial power in the world. Today, this empire is clearly declining. It is breaking up.” (Rouge, August 11, 1978, on the occasion of the sale of Chrysler/Europe to Peugot-Citroën.)

This way of looking at things is incorrect, because it is too one sided. In reality, the U.S. automotive industry has only been seriously worried by the competition from Japan and the Common Market. It experienced certain difficulties in responding to the offensive and restructuring mentioned above. But subsequently, at least two of the American giants – Ford and GM – have taken up the challenge. And at present their chances for tightening the screws on their European competitors and pushing back the Japanese are far from unfavorable. The General Motors and Ford trusts have, in fact, three big advantages over their rivals:

They have, first of all, big plants in Western Europe already, and so they do not have to set about building any now. As long ago as 1929, GM bought the German Opel company, which today is the second largest producer of automobiles in West Germany. In Britain, it owns Vauxhall, and in Australia Holden. It employs 130,000 workers in twenty-one European factories and has the capacity to assemble 1.5 million vehicles (VW in the United States produces barely 200,000!). It accounts for 10% of the total production of cars in Europe. Ford, the no. 2 producer in the United States, has even passed GM in Europe. It has been engaged in a still more powerful process of concentration.

|

In 1967, Ford had already combined its fifteen European companies under the roof of “Ford of Europe.” In 1975, the U.S. automotive trusts controlled 52% of British automotive production, 31% of West German production, and 13% of French production. This is an advantage that its European competitors themselves do not have. (Economic et Statistique, op. cit. The figures reflect the situation before Chrysler/Europe was bought out.)

Secondly, the two American giants have a clear superiority in productive capacity over their rivals. GM alone produces 6.7 million vehicles, more than the three biggest European producers put together. (Peugot-Citroen combined with Chrysler/ Europe produces 2.3 million; Volkswag-en/Audi NSU, 2.2 million; Renault-Saviem-Berliet, 1.8 million.) Of course, such giant size may not always be an advantage, especially if this trust does not succeed in really concentrating its productive capacity. [3]

But once such a concentration exists, and today competition is forcing all the American producers to concentrate their productive capacity, bigness pays. Ford and GM have just coordinated their respective production shops and have perfected the conception of what they call “world cars.” These are basically the same car, sometimes with modifications, disguised by different styling. That is, they have the Bame motors, transmissions, and chassis. These models are built in all the plants that belong to the trust, throughout the world, in a largely standardized way.

The advantages of this are clear: The parts are interchangeable. The costs are lower due to economies of scale. And it is easy to make adjustments to adapt to the fluctuations of demand in the market. Finally, there is still another advantage. This flexibility is also an invaluable help in the event of workers struggles.

When an English factory, for example, goes on strike, Ford can shift production to Spain, Belgium, or West Germany without any technical problems. [4]

Thirdly, the two American trusts have a financial potential much greater than their rivals. Their investment programs, moreover, are on a scale commensurate with this power. In June 1979, GM pointed up the possibilities for financing and investing that these two world giants had.

After having already decided in 1977 to expand the factories owned by its West German subsidiary Opel by allocating an investment program of 5 billion Marks, GM decided in 1979 to launch a new 4 billion-Mark program to build two new factories in Spain (in Saragossa, and Puerto Real near Cadiz), as well as an engine factory in Austria. Thus, the funds that GM allocated just to these European programs totalled more than the overall investment programs of almost all its competitors. The same can be said about the investment of Ford/Europe, but in this case there are as yet no detailed figures. [5]

Under the impact of this U.S. offensive, the boss of the FIAT corporation, Agnelli, has said: “The European automotive companies should get together to collaborate more closely in the face of the threat from across the Atlantic” (Wirtschaftwoche, June 25, 1979). Good advice, but the car makers in the Common Market are acting differently. A competitive war has broken out throughout the European auto market. The various trusts are drawing up oversized programs. One thing that can be said with certainty about these plans is that taken together they involve the creation of enormous surplus capacities.

This incomplete survey of investment (it leaves out the detailed programs of the French producers) enables us to estimate here and now that the total investment for the period ending in 1983 will be 35 billion Marks. In 1979 and 1980, investments should total more than 10 billion Marks. In 1979, European productive capacity is about 12 million vehicles annually. EuroFinance expects, as a result of the new investment programs, that the maximum capacity in 1982–83 will be 13 million. But today, despite the economic boom, only 10.5 million vehicles are being sold annually.

The picture grows still darker when you consider the situation on the export market. The Japanese producers have made concentrated efforts to increase their share in Western Europe. In West Germany alone in two years, 1977–79, they have managed to double their sales to about 125,000 vehicles.

At the same time, the Japanese have doubled their share of the market, which rose to 4.2% in 1978 and an estimated 4.5% for 1979. In the process, they have changed their traditional image as “exporters of cheap cars” and won a new layer of customers by selling very expensive automobiles (this is the explicit intention of Mitsubishi, a “new Japanese Mercedes”).

The “new cheap imports” are coming today from the East European countries and this year they started coming from South Korea as well. The most famous of these cars is the Lada, which is produced in the Soviet Union in a plant built under FIAT license (the Vaz factory in Togliattigrad). Now, in view of the competition these cars are offering on the export market, the capitalists are no longer so happy about this example. The Soviet factory produces 800,000 vehicles every year, and it exported 300.000 of these in 1977, mainly to Western Europe. These sales produced 3 billion Marks revenue for the USSR (Wirtschaftswoche, November 24, 1978).

More recently, a Romanian plant, set up by Renault, has begun to play a certain role (Le Monde, July 3, 1979). The imports from the East European countries are priced 1,000 to 2,000 Marks cheaper than the competing models produced in Western Europe.

The new capitalist exporter of cheap cars is Hyundai Motor Company, based in Seoul, South Korea. [6] Of course, this company is only producing 100,000 vehicles today and only exporting a few thousand vehicles to Belgium, Holland, and Greece. However, its planned investments would enable it to make a breakthrough in 1982, with a capacity of 730,000 vehicles.

The 4,000 Mark price tag on the “Pony” model is extremely low by comparison with the price and quality of competing models, although the best that the Korean company can hope for is to break into the European markets in the early 1980s (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, November 27, 1978).

Today, we are seeing the crystallization in the automotive industry of a series of general structural elements in the crisis of declining capitalism and of the coming recession. In spite of, and partially because of, the deep recession of 1973–74, a new overheating is evident. In 1975–76, the existing capacity was more and more fully utilized. Then, there was a new rise of investment from 1977 to 1979. This explosion has come in the context of increased international competition. It has been evolving in a totally anarchic way, and is creating, as has already been noted, gigantic surplus capacities.

Since 1978, a new inflationary process has been developing. The relative absence of unutilized surplus capacity has accelerated profits, because relatively growing demand in the market has created very favorable conditions. But these conditions are precisely the factors that are going to touch off the new crisis of the automotive industry in 1980 or 1981 – that is, the excess capacity planned today and the decline of solvent demand.

The situation remains favorable, even highly favorable, for making profits and will probably remain so in the near future. (For example, in 1979, VW enjoyed a 5 billion Mark liquidity.) Conditions will deteriorate only when the processes described mature. In the coming crisis, unutilized capacity will result in a fall in the rate of profit.

So, why will a decline in demand be the first factor to touch off the crisis? In this area as well, the automotive industry has proved representative of the general imperialist structure. The new economic boom has created only few, if any, new jobs. At the same time, it can be seen that real wages have risen hardly at all, in accordance with the stabilization policy practiced internationally.

At the beginning, the new investments were devoted exclusively to increasing the efficiency of production. It was only at the start of 1979 that investment began to be directed toward expanding production. But this was done everywhere on the basis of a very high level of technology, thereby involving savings in labor power. [7] So, this new investment went hand in hand with an intensification of labor. A few figures will demonstrate this.

In 1979, despite increased production and large investment, British Leyland further reduced its workforce by 15,000 workers and before the end of the year it expects to lay off another 5,000. This amounts to an 18% reduction in the workforce. New massive cutbacks in employment were announced in September 1979.

The Volkswagen trust increased its general sales by 62.5% between 1974 and 1978. On the other hand, its labor costs increased only by 38.9% for the same period. In 1978, the VW workforce was on the average 5% lower worldwide and 11% lower in West Germany than it was in 1974 (Handelsblatt, May 5, 1979).

In trusts such as British Leyland, and Peugeot-Citroën now that it has bought out Chrysler/Europe, and FIAT now that it has bought into SEAT (a Spanish car maker), the threat of layoffs hang over the workers like the sword of Damocles. These companies are going to have to reduce their workforces in order to hold their own in international competition.

The same is true for Alfa Romeo. At the end of July 1979, it was announced that this nationalized company was for sale, that is, that it was going to be reprivatized. Despite a massive increase in production (more than 20% in 1978), Alfa Romeo suffered big new losses (126 billion lira in 1978).

To be sure, these plans for reprivatization were dropped as a result of the protests they aroused. But the fact remains that it has been confirmed that Alpha was “looking for a financially sound Italian or foreign partner.” The partner they want is FIAT. How this affair ends is of little importance. The fact is that here too, gigantic restructuring is being carried out, that is, they are laying off workers (Neue Zücher Zeitung, July 29, 1979).

In the United States, General Motors has made it clear that gigantic investment programs and an export offensive do not at all mean job security for the workers. On July 30, 1979, this automotive giant announced the lay-off of 12,600 workers in the U.S. At Ford by midyear layoffs totalled 14,000; and at Chrysler, 19,500 [8] (Neue Zürcher Zeitung, July 31, 1979). And, it should be noted well, this was in a big boom year in the automotive industry.

This new boom is a reality only on the credit side of the bosses ledgers. The workers face the threat once again of having to bear the whole burden of the new crisis. If today, in the middle of an overheated economic picture the number of workers is lower than it waB during the last overheated phase, it can easily be envisaged that the layoffs in the new crisis will be more massive than they were in the crisis of 1973–75.

Today already the Common Market commission in Brussels is predicting that “hundreds of thousands of jobs” will be threatened in the automotive industry of member countries. Only a struggle for a shorter workweek and for dividing the work among all offers the workers in the auto industry, as well as in the rest of the imperialist economy, a real chance to fight back.

Beyond this question, the problem of the international coordination of the defense of the workers’ struggles arises. Here again the auto industry offers an instructive example. The internationalization of VW’s production means, for instance, that only a broad network of trade unions active in the VW concerns throughout the world can counter the plans of the management.

In this regard, the June 1979 reactiviza-tion of the World Auto Commission for VW in the framework of the International Federation of Metalworkers (FIOM) was certainly a step forward. But direct action is more important than summit conferences of plant delegates and union functionaries.

The FIAT trust and the FIAT workers demonstrated the possibilities for such a struggle in June and July 1979. At that time, as a result of the strikes by the Italian FIAT workers, the company wanted to ship in cars built in Spain (by SEAT) and in Brazil. The stevedores, however, refused to unload the cars and defeated this operation. Finally, the company’s attempt to bring the cars in over the roads was blocked by the resistance of the French unions.

1. Mandel/Wolf, Ende der Krise, Berlin 1977.

2. There is reason to believe that the rumors that Chrysler was going to be bought out by VW were set in motion by Chrysler itself, with the aim of forcing the U.S. government to take measures to shore up Chrysler and to get financial support. On the other hand, another argument can be made against the rumors that Chrysler is going to be bought out entirely by VW. Chrysler produces not just cars but also MX 1 assault tanks. So, the buying out of this corporation by a foreign company would be detrimental to “the interests of American security.”

3. This is why GM undertook such a process of concentration only belatedly. Moreover, the new Peugot-Citroën group has one specific weak point. The trust either has to make drastic adjustments to meet competition, or it will go into a structural crisis under the blows of competition. The British Chrysler workers have pointed out that a policy by the company oriented toward competition and profits was in direct contradiction with the interests of the workers. After learning of the merger, they got an assurance that there would be no firings.

4. The “world car” concept is also one of the causes of VW’s new success. The “Bug” has now been replaced by the Golf (Rabbit) “world car” and the Polo-Passat-Dasher-Sirocco-Derby line. The other new cars in the VW group that are in themselves fully competitive but do not fit this conception are being strictly limited to one segment of the auto market. VW’s Audi subsidiary, for example, is concentrating more and more on luxury cars and thus is trying to compete with Mercedes-Benz and BMW.

5. Der Spiegel has reported that VW has also gotten orders for engines for the Ford factories in the U.S. Even if thia were true, which seems hardly likely given Ford’s investment program, this operation could in no way be compared with the VW-Chrysler cooperation. In the case of Ford, it could only be a temporary solution that would prepare the way for a still more effective offensive by this trust (Der Spiegel, June 16, 1979).

6. This is the automotive branch of the most powerful Korean company (which, however, ranks eighty-ninth on the list of the world’s big capitalist trusts). Its automotive production is carried out in cooperation with the Japanese company Mitsubishi.

7. Since 1978, they have begun to use automatic machinery on a large scale in the automotive industry, among other things, for spot welding. It should be noted, moreover, that it is symptomatic that the German automotive industry first used automated machines to build the Ford “world car,” the Fiesta (at the Saarlouis factory). This began in 1977. Today VW is the leader in West Germany in this technique of production. In its factories, there are about 100 automated machines. VW itself makes them. This is the reason for its relationship with the computer company, Adler-Triumph.

8. By early November, total announced lay-offs by the American Big Three were: GM, 37,250; Ford, 53,800; Chrysler, 29,000. – IP/I.

Winfried Wolf Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 13 June 2023